1

Ives playing Ives - a decidedly lo-fi recording, but Ives brings a certain I-don't-know-what to his own composition ("The Alcotts" section of the Concord Sonata) that isn't present in any other version I've heard.

2

Speaking of 20th-century composers, if I ever become a full-time aesthete, haunting avant-garde salons and whatnot, I plan to adopt this look. Hearing this Boulez recording of Ionisation recently made me wonder if Brian Wilson was listening to Varèse around the time of Pet Sounds and the original Smile sessions. To me, there are some clear similarities - the layering of different percussion instruments and, of course, the use of fire sirens and (though not in Ionisation) theremins. I think there's something about the reverby room sound on the Boulez version that makes me think of the sounds Wilson was getting at Gold Star and Western Recorders. In other versions of Ionisation, I don't hear the connection as much. The Varèse-Zappa connection has been well documented (and the Varèse-Bird connection!), but, perhaps unsurprisingly, I've never heard Varèse mentioned in the same sentence as the Beach Boys.

3

Any list of the greatest guitar riffs of all time that does not include some version of Johnny Kidd & The Pirates' "Shakin' All Over" is not to be taken seriously. Check out Jimmy Page trying to remember it here.

4

Last week, I saw a screening of Glenn Ligon's film The Death of Tom at the Whitney, attracted by the prospect of hearing the score performed (actually spontaneously re-composed) by Jason Moran. The film and Moran's performance were worth walking through a hail storm for, and I got a lot out of the discussion after the screening. The topics included Ligon and Moran's mutual love of Monk; Ligon's artistic decision to let his original conception of the film go and yield to the opportunities afforded by an epic camera/film stock fail and Moran's music, ending up with a very different film than he'd envisioned; and Moran and the Bandwagon's ongoing process of wrestling with Bert Williams' massive-for-its-time hit "Nobody" (a hidden track on Ten and a main motif in Moran's Death of Tom music), with renditions often breaking into violent deconstruction and stopping just short of total destruction. There's a good interview of Ligon, conducted by Moran and covering some of the same topics as the Whitney discussion, here.

5

I recently found a great anecdote from the history of architecture that says something about the 20th-century tendency toward refinement (in the sense of removing impurities, extraneous elements) in design (although both of the architects in question were often less restrained in practice than the anecdote may suggest). To tangentially relate this last item to music, I'll note that it comes via the website of Ken Vandermark, the great Chicago saxophonist who I saw recently with Joe Morris and a couple years ago with Jason Moran.

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

Five Music-Related Items

Labels:

architecture,

art,

links,

music,

youtube

Friday, March 18, 2011

Chelsea USA

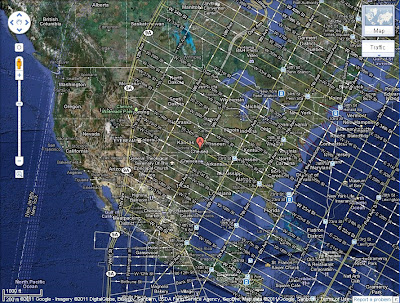

Google Maps has been acting up lately, at least for me. One result was this map, improbably superimposing Chelsea over the entire United States, creating a fun alternate reality in which the Hotel Gansevoort is located on the outskirts of Guadalajara:

Labels:

geography fail,

google anomalies,

maps

Thursday, March 17, 2011

Your Face Tomorrow

I finished the final volume of Javier Marías' Your Face Tomorrow over the weekend. I'm definitely not done thinking about it, but I might venture a few tentative thoughts.

The structure of this three-volume,1200+ page work is one of the most intriguing things about it. I'd like to see somebody chart the plot of YFT, to show how frequently the action jumps backward in time only to return to the main story, the whole of which is being related after the fact by the narrator/protagonist. [The chart probably wouldn't need to be as complicated and this or this. Maybe it would look something like this.] This narrator, Jacques Deza, comments several times on how a few of the main characters, himself included, share the ability to never "lose the thread", no matter how many tangents they follow or parentheses they insert into a conversation. And this is exactly what Marías does. Although the timeline of the main story may only advance by a matter of minutes in hundreds of pages, as happens in the second volume, Marías/Deza never lets go of the thread, always finding his way back from the innumerable digressions, asides, speculations, backfills, and recollections within recollections. In retrospect, it becomes clear that the digressions are really just as much part of the story, just as important, as the main thread. Though the material is much different, the way that stories lead to other stories, or memories to other memories, in YFT is not unlike the book-within-a-book in Michal Ajvaz's The Golden Age (which I discussed here), with the key difference that Ajvaz's narrator does lose the thread as he's pulled deeper and deeper into "the Book".

The pace of YFT's main story seems to pick up a bit in the third (and longest) volume, as Marías starts to pay off on a lot of things he'd set up much earlier - hints, allusions, questions, obsessively repeated words or quotations of initially unclear import. Still, the bare facts of the plot could have been related in conventional novelistic fashion in a matter of a few hundred pages, even taken at a leisurely pace, pausing frequently to describe rooms and sunsets. So what does Marías need three volumes for? I wouldn't call YFT an experimental novel. Structurally, Marías is not doing anything more radical than Proust (and certainly less radical than Sterne). He does, however, find a way of representing his narrator's consciousness, his internal monologue, that may not be new but certainly is distinctive and effective. The voice and storytelling method Marías has fashioned is even, to indulge in a book jacket blurb cliche, compulsively readable despite the sheer length that results from this approach. If you can get on Marías' wavelength in the first book, you'll be with him for the long haul, all the way to the end of his epic London-Madrid sort-of-spy story.

With YFT, Marías makes a case for the novel's continued relevance as a form uniquely suited to shed light on the mysteries of human consciousness and human behavior. I'm pretty sure he's also given us some deep insights on the perennial (and interrelated) subjects of history, memory, war, and violence, but these (especially the last two) are the aspects of the book that I feel I'm still unpacking, and writing about them would probably merit a whole separate (and much longer) post.

[After finishing this post, I've started working my way through the series on YFT at Conversational Reading, which I'd specifically avoided - along with almost all reviews - until I finished the book.]

The structure of this three-volume,1200+ page work is one of the most intriguing things about it. I'd like to see somebody chart the plot of YFT, to show how frequently the action jumps backward in time only to return to the main story, the whole of which is being related after the fact by the narrator/protagonist. [The chart probably wouldn't need to be as complicated and this or this. Maybe it would look something like this.] This narrator, Jacques Deza, comments several times on how a few of the main characters, himself included, share the ability to never "lose the thread", no matter how many tangents they follow or parentheses they insert into a conversation. And this is exactly what Marías does. Although the timeline of the main story may only advance by a matter of minutes in hundreds of pages, as happens in the second volume, Marías/Deza never lets go of the thread, always finding his way back from the innumerable digressions, asides, speculations, backfills, and recollections within recollections. In retrospect, it becomes clear that the digressions are really just as much part of the story, just as important, as the main thread. Though the material is much different, the way that stories lead to other stories, or memories to other memories, in YFT is not unlike the book-within-a-book in Michal Ajvaz's The Golden Age (which I discussed here), with the key difference that Ajvaz's narrator does lose the thread as he's pulled deeper and deeper into "the Book".

The pace of YFT's main story seems to pick up a bit in the third (and longest) volume, as Marías starts to pay off on a lot of things he'd set up much earlier - hints, allusions, questions, obsessively repeated words or quotations of initially unclear import. Still, the bare facts of the plot could have been related in conventional novelistic fashion in a matter of a few hundred pages, even taken at a leisurely pace, pausing frequently to describe rooms and sunsets. So what does Marías need three volumes for? I wouldn't call YFT an experimental novel. Structurally, Marías is not doing anything more radical than Proust (and certainly less radical than Sterne). He does, however, find a way of representing his narrator's consciousness, his internal monologue, that may not be new but certainly is distinctive and effective. The voice and storytelling method Marías has fashioned is even, to indulge in a book jacket blurb cliche, compulsively readable despite the sheer length that results from this approach. If you can get on Marías' wavelength in the first book, you'll be with him for the long haul, all the way to the end of his epic London-Madrid sort-of-spy story.

With YFT, Marías makes a case for the novel's continued relevance as a form uniquely suited to shed light on the mysteries of human consciousness and human behavior. I'm pretty sure he's also given us some deep insights on the perennial (and interrelated) subjects of history, memory, war, and violence, but these (especially the last two) are the aspects of the book that I feel I'm still unpacking, and writing about them would probably merit a whole separate (and much longer) post.

[After finishing this post, I've started working my way through the series on YFT at Conversational Reading, which I'd specifically avoided - along with almost all reviews - until I finished the book.]

Labels:

books

Monday, March 7, 2011

Soul In The Night & Other Finds

Perhaps the most interesting find on my most recent visit to the Jazz Record Center was a mid-sixties Sonny Stitt-Bunky Green session called Soul In The Night (with future Earth, Wind & Fire leader Maurice White on drums!). While this album is squarely in the soul jazz/organ jazz tradition, from an era when presumably these tunes might've shown up on Chicago jukeboxes, Bunky Green's eventually quite influential (on Greg Osby, Steve Coleman, and Rudresh Manhanthappa, among others) approach on alto is very much in evidence, and the pleasing contrast with Stitt brings it into sharp relief. While some of the tunes seem a bit dated in their Swinging Sixties-ness (at certain points, you can almost picture Austin Powers doing The Frug), there's some real meat here, as on the Stitt-composed simple blues blowing vehicle "Home Stretch", where the two altos stake out their respective aesthetic positions with some nice trading.

Green was still playing "inside" by almost any definition, but with a slight kink or skew away from the mainstream and the alto tradition represented at that time by Stitt, the great Bird torch carrier.

It might be a stretch to call Soul In The Night a template for the Green-Manhanthappa dual alto disc Apex, but I think it would certainly make for an interesting back-to-back listen, and there is a nice bookend quality, with Green having been the young up-and-comer on Soul In The Night and the respected elder on Apex. [When I started writing this, I had no idea that this fantastic Manhanthappa on Green post was going up at Destination: Out.]

In the Record Center's "bargain bin", where surprising treasures lurk, I found the legendary-in-certain-circles Furry Lewis Fourth & Beale, recorded by the also legendary-in-certain-circles Memphis producer Terry Manning with the artist sitting in bed with his wooden leg off. There's a newer version out there with more tracks than this disc has, but for $5 I can't complain - I'd probably pay five bucks for a blank disc if it had Stanley Booth liner notes. I also picked up an album of Kurt Weill songs by Tethered Moon, the trio of Masabumi Kikuchi, Paul Motian and Gary Peacock, the first two of which will be at the Village Vanguard this week.

Green was still playing "inside" by almost any definition, but with a slight kink or skew away from the mainstream and the alto tradition represented at that time by Stitt, the great Bird torch carrier.

It might be a stretch to call Soul In The Night a template for the Green-Manhanthappa dual alto disc Apex, but I think it would certainly make for an interesting back-to-back listen, and there is a nice bookend quality, with Green having been the young up-and-comer on Soul In The Night and the respected elder on Apex. [When I started writing this, I had no idea that this fantastic Manhanthappa on Green post was going up at Destination: Out.]

In the Record Center's "bargain bin", where surprising treasures lurk, I found the legendary-in-certain-circles Furry Lewis Fourth & Beale, recorded by the also legendary-in-certain-circles Memphis producer Terry Manning with the artist sitting in bed with his wooden leg off. There's a newer version out there with more tracks than this disc has, but for $5 I can't complain - I'd probably pay five bucks for a blank disc if it had Stanley Booth liner notes. I also picked up an album of Kurt Weill songs by Tethered Moon, the trio of Masabumi Kikuchi, Paul Motian and Gary Peacock, the first two of which will be at the Village Vanguard this week.

Labels:

blues,

compulsive acquisition,

jazz,

music

Wednesday, March 2, 2011

Thoughts on Some Recent Shows (+ Amazon Knucklehead Dilution Project)

In the last couple weeks, I've had the opportunity to see three of the most exciting contemporary drummers on the New York scene: Tom Rainey (with guitarist Nir Felder), Ches Smith (with his These Arches group), and the man who has fit that description for over 50 years, Paul Motian (with a quintet). Rainey was the only one of the three that I hadn't seen before and he was extremely impressive, employing a full range of techniques (including playing with his bare hands) with a concentrated focus - you can see Rainey listening and the results, whether subtle accents or controlled explosions, consistently elevate the music being played (Rainey is truly onto some "next level sh*t"). I would think Felder's music must sound very different when he plays with any other drummer.

I'd seen Ches Smith before (with Mary Halvorson and in Marc Ribot's Ceramic Dog), but I don't think I'm ever quite prepared for him. One of the most fascinating drummers to watch, there is something very visual about his style, simultaneously free/out/avant and rock-oriented. He seems to have a special mind meld with Mary Halvorson, finding just the right weird thing to perfectly accompany whatever weird thing she's playing at a given time (and to be clear, weird is to be taken as an endorsement of this music). This was my first time hearing a set of Smith's compositions, and though I probably can't describe them adequately (they were pretty diverse), I definitely want to hear more.

I've written plenty about Paul Motian, but there was one moment toward the end of the recent set I saw at the Village Vanguard when the sound coming from his corner of the stage was just amazing. He really had the whole kit simmering with an utterly distinctive combination of (among other sounds) "pish"ing cymbal, clattering sticks, and a sound that reminded me of kicking the side of a file cabinet. As I said about Fred Hersch's piano sound at the Vanguard, I don't think any recording I've heard of Motian has quite captured what he sounds like in that room.

After seeing Motian's quintet last weekend (he's at the Vanguard for two more weeks with two different groups), I think I can feel a major Bill McHenry phase coming on. McHenry's use of space with Motian was one of the more striking features of the group's sound. He built up solos gradually, deliberately, from short phrases separated by pauses that seemed almost uncomfortable (like pauses in a conversation that last just a little too long) to longer, more sustained runs, whether languid or fleet - it was edge-of-the-seat dramatic and wholly successful.

The entire quintet impressed me with how fluent they were in Motian's language, with McHenry and pianist Russ Lossing perhaps most outstanding in this regard. Distinctively Motian-esque phrases kept cropping up in the midst of improvisation (certainly on Motian's own tunes - the set I saw seemed to follow a strict pattern of alternating Motian compositions with standards). Some of this was just a matter of improvising on the melodies, but at other times, it really felt like these players were really thinking like Motian, they'd absorbed his compositional language and now sounded like natural, native speakers.

And while I'm on the subject of great contemporary New York-based improvising musicians, I should point out an injustice of sorts that's recently come to my attention. I noticed yesterday that Jason Moran's pretty much universally praised Ten, consensus best jazz album of 2010, currently has a three-star (out of five) rating on Amazon. This matters because it could potentially keep people away from discovering this album. People who may not be familiar with Moran's work or only know his earlier stuff might actually give credence to the two (in my opinion) wildly misguided two-star reviews and miss out on some great music. Surely Ten had more than four total reviews at one time, but now it seems that it's being sold through an Amazon affiliate and Amazon has wiped all the previous reviews and started from scratch, so that these two bad reviews really stand out and have undue weight. So, what I'm proposing is that any fans of Ten reading this follow this link and review it. Let's right an aesthetic wrong here. (And maybe somebody with a blog readership exceeding mine can pick this up and make it a mini-campaign.)

Bonus Links

I found a great Bill McHenry audio interview (along with two streaming live sets) here.

And a sweet YouTube find: McHenry Sings Carmichael! (in Spain, while looking a lot like Mad Men's Paul Kinsey)

I'd seen Ches Smith before (with Mary Halvorson and in Marc Ribot's Ceramic Dog), but I don't think I'm ever quite prepared for him. One of the most fascinating drummers to watch, there is something very visual about his style, simultaneously free/out/avant and rock-oriented. He seems to have a special mind meld with Mary Halvorson, finding just the right weird thing to perfectly accompany whatever weird thing she's playing at a given time (and to be clear, weird is to be taken as an endorsement of this music). This was my first time hearing a set of Smith's compositions, and though I probably can't describe them adequately (they were pretty diverse), I definitely want to hear more.

I've written plenty about Paul Motian, but there was one moment toward the end of the recent set I saw at the Village Vanguard when the sound coming from his corner of the stage was just amazing. He really had the whole kit simmering with an utterly distinctive combination of (among other sounds) "pish"ing cymbal, clattering sticks, and a sound that reminded me of kicking the side of a file cabinet. As I said about Fred Hersch's piano sound at the Vanguard, I don't think any recording I've heard of Motian has quite captured what he sounds like in that room.

After seeing Motian's quintet last weekend (he's at the Vanguard for two more weeks with two different groups), I think I can feel a major Bill McHenry phase coming on. McHenry's use of space with Motian was one of the more striking features of the group's sound. He built up solos gradually, deliberately, from short phrases separated by pauses that seemed almost uncomfortable (like pauses in a conversation that last just a little too long) to longer, more sustained runs, whether languid or fleet - it was edge-of-the-seat dramatic and wholly successful.

The entire quintet impressed me with how fluent they were in Motian's language, with McHenry and pianist Russ Lossing perhaps most outstanding in this regard. Distinctively Motian-esque phrases kept cropping up in the midst of improvisation (certainly on Motian's own tunes - the set I saw seemed to follow a strict pattern of alternating Motian compositions with standards). Some of this was just a matter of improvising on the melodies, but at other times, it really felt like these players were really thinking like Motian, they'd absorbed his compositional language and now sounded like natural, native speakers.

And while I'm on the subject of great contemporary New York-based improvising musicians, I should point out an injustice of sorts that's recently come to my attention. I noticed yesterday that Jason Moran's pretty much universally praised Ten, consensus best jazz album of 2010, currently has a three-star (out of five) rating on Amazon. This matters because it could potentially keep people away from discovering this album. People who may not be familiar with Moran's work or only know his earlier stuff might actually give credence to the two (in my opinion) wildly misguided two-star reviews and miss out on some great music. Surely Ten had more than four total reviews at one time, but now it seems that it's being sold through an Amazon affiliate and Amazon has wiped all the previous reviews and started from scratch, so that these two bad reviews really stand out and have undue weight. So, what I'm proposing is that any fans of Ten reading this follow this link and review it. Let's right an aesthetic wrong here. (And maybe somebody with a blog readership exceeding mine can pick this up and make it a mini-campaign.)

Bonus Links

I found a great Bill McHenry audio interview (along with two streaming live sets) here.

And a sweet YouTube find: McHenry Sings Carmichael! (in Spain, while looking a lot like Mad Men's Paul Kinsey)

Labels:

amazon review trolls,

drums,

jazz,

music

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)